Pharmacological and Parental Therapies / 04

Make sure to:

- Grasp the basic concepts and principles of pharmacology.

- Recognize the effects of drugs on the human body.

- Explore the various processes in each organ and system that modify or transform drugs once they reach circulation.

- Understand key concepts about this topic such as drug effects, drug side effects, pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, drug concentration and excretion.

According to Chen et al. (2018), in the 16th century, a Swiss physician named Paracelsus coined the expression "the dose makes the poison", which is not only an intriguing idea but also the foundation of pharmacology. The study of how a substance can interact with the body, whether in favor or against it, presents both benefits and risks. For example, drinking water is beneficial for the body, but attempting to consume 50 gallons of water in one hour can be fatal. Paracelsus's words remain true.

According to Chen et al. (2018), in the 16th century, a Swiss physician named Paracelsus coined the expression "the dose makes the poison", which is not only an intriguing idea but also the foundation of pharmacology. The study of how a substance can interact with the body, whether in favor or against it, presents both benefits and risks. For example, drinking water is beneficial for the body, but attempting to consume 50 gallons of water in one hour can be fatal. Paracelsus's words remain true.

From his time to the present, numerous technological advances have occurred: chemical principles have been refined, the mass production of pills has become more efficient, and organized international trials are now commonplace. However, a fundamental principle of pharmacology persists from many centuries ago: with proper education and the application of knowledge, healthcare professionals can administer precise dosages of ingredients to alleviate the suffering of patients.

1.1 Drug Principles

The key principles for pharmacology may initially seem challenging to grasp, but they serve as the fundamental foundation for understanding the workings of various drugs, their intended effects and side effects. A strong understanding of this subject forms a solid basis for everything related to drugs. It is important to remember that effective medication management requires an interprofessional team of healthcare professionals, and as a result, “without proper medication management, morbidity and mortality from various health conditions can be high” (Chen et al., 2018). A comprehensive and accurate understanding of drug absorption and its dynamics once it enters circulation is crucial. Adequate knowledge of drug absorption enables nurses to advocate for patients and effectively communicate with the multidisciplinary healthcare team, collaborating with other healthcare professionals to improve patient health outcomes.

The key principles for pharmacology may initially seem challenging to grasp, but they serve as the fundamental foundation for understanding the workings of various drugs, their intended effects and side effects. A strong understanding of this subject forms a solid basis for everything related to drugs. It is important to remember that effective medication management requires an interprofessional team of healthcare professionals, and as a result, “without proper medication management, morbidity and mortality from various health conditions can be high” (Chen et al., 2018). A comprehensive and accurate understanding of drug absorption and its dynamics once it enters circulation is crucial. Adequate knowledge of drug absorption enables nurses to advocate for patients and effectively communicate with the multidisciplinary healthcare team, collaborating with other healthcare professionals to improve patient health outcomes.

There are well-known general principles, including:

- Over-the-counter drugs: These are medications that patients can purchase without the need for a medical prescription.

- Prescription drugs: As the name indicates, these require a physician prescription, which include directions for use.

1.2 Pharmacokinetics

Pharmacokinetics “is the part of pharmacology that deals with time required for drug absorption, distribution in the body, metabolism, and method of excretion/elimination”. To simplify the concept, it focuses on how a patient’s body is affected by the drug. According to Meloni and Mastenbjörk (2021) “processes such as absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion are described by pharmacokinetic parameters”.

Pharmacokinetics “is the part of pharmacology that deals with time required for drug absorption, distribution in the body, metabolism, and method of excretion/elimination”. To simplify the concept, it focuses on how a patient’s body is affected by the drug. According to Meloni and Mastenbjörk (2021) “processes such as absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion are described by pharmacokinetic parameters”.

Drug absorption, one of the most relevant principles in pharmacokinetics, is described in the literature as the transportation of the unmetabolized drug, the drug, in its pure form, from the site of administration (oral, intravenous, intramuscular) to the body’s circulation system.

The most common route of absorption, which is associated with being the most common form of drug administration, is the oral route, often abbreviated in the medical charts as “PO”. Therefore, an understanding of factors that influence oral absorption is important. For a drug to enter the systemic circulation following oral administration, it must first dissolve, cross the intestinal membrane, and pass through the liver (Meloni & Mastenbjörk, 2021).

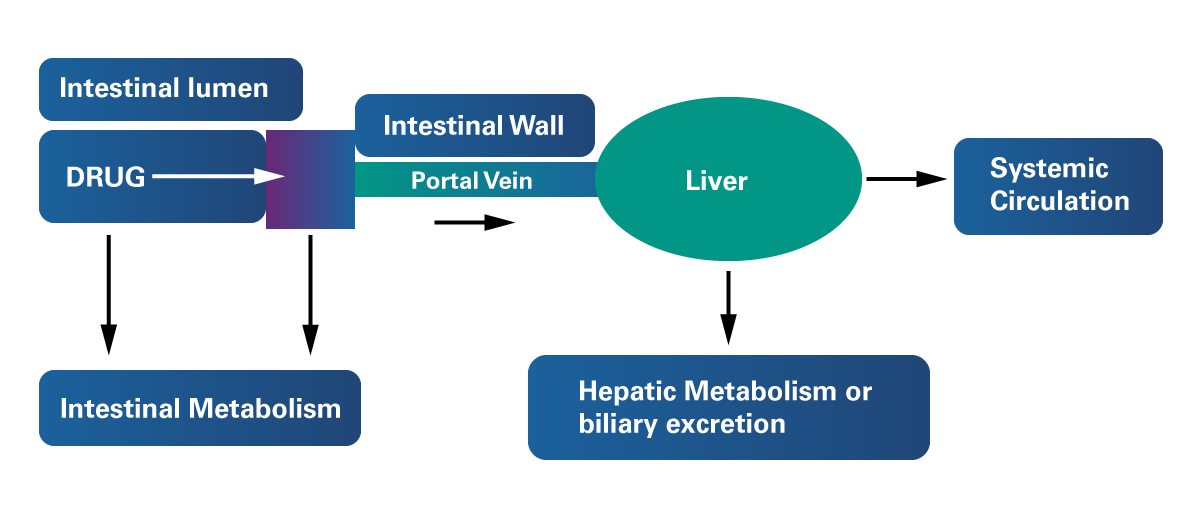

For a drug that is intended to follow the oral route of absorption to enter the systemic circulation, “it must be absorbed through the intestinal wall, enter the portal vein, pass through the liver, and enter the systemic circulation” (Meloni & Mastenbjörk, 2021). Figure 1 shows the pathway of absorption followed by an oral drug after administration.

Figure 1

Mechanism of Liver Absorption

Adapted from Ticho et al. (2019). Intestinal Absorption of Bile Acids in Health and Disease. Comprehensive Physiology, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c190007

Adapted from Ticho et al. (2019). Intestinal Absorption of Bile Acids in Health and Disease. Comprehensive Physiology, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c190007

According to Zerwekh and Garneau (2021), metabolism occurring within the intestinal lumen and liver before reaching the systemic circulation is known as “First-pass metabolism”. This feature of the hepatic metabolism also contributes to the elimination of a several drugs and drug families. Throughout this process, drugs ingested orally reach the liver directly through the portal vein, where they undergo biotransformation prior entering the systemic circulation. This process reduces the bioavailability of orally administered drugs. In contrast, intravenously administered drugs do not undergo the first-pass effect.

Bioavailability refers to the extent to which an extravascular (e.g., oral, subcutaneous, intraperitoneal, etc.) dose is available in the systemic circulation in comparison to an intravenous dose. In simpler terms, it represents the fraction of the active drug that reaches the bloodstream.

According to Meloni and Mastenbjörk (2021), clearance (CL) is the volume of blood cleared of compound/drug per unit time. CL is expressed in volume/time (i.e., mL/min). CLs by various organs are additive. The total body CL of a compound is the sum of the CL contributions from various organs.

Drug-metabolizing enzymes (DMEs), the body’s biologic catalyst, are predominantly found in the liver, intestine, and blood. They are responsible for converting lipophilic, fat-bonded drugs into more hydrophilic compounds, making it easier for the body to excrete them.

Other organs and systems are also involved in metabolism, including extrahepatic metabolism, which occurs in the GI tract, kidneys, lungs, plasma, and skin.

Elimination of drugs

The removal of an administered drug from the body is known as drug elimination, and this process can occur in two ways:

- Excretion of an unmetabolized drug in its unchanged form.

- Metabolic biotransformation followed by excretion.

According to Garza et al. (2023) excretion takes place in the kidneys; however, other organ systems also play a role. In the same vein, the liver serves as the primary site of biotransformation, but extrahepatic metabolism occurs in other organ systems, affecting multiple drugs.

According to Garza et al. (2023) excretion takes place in the kidneys; however, other organ systems also play a role. In the same vein, the liver serves as the primary site of biotransformation, but extrahepatic metabolism occurs in other organ systems, affecting multiple drugs.

Renal excretion is the elimination process that follows the one initiated in the liver. Polar drugs or their metabolites undergo glomerular filtration in the kidneys and typically do not undergo reabsorption, subsequently being excreted in the urine.

According to Garza et al. (2023) excretion in the bile is another significant method of drug elimination. The mucosa and various organs and tissues also contribute to different pathways of excretion, including the lungs, breast milk, sweat, saliva, and tears.

- Medications for patients or clients aged over 65:

Elderly patients may be prone to a decrease in both liver and kidney function.

According to Cleveland Clinic (2023), the Beers Criteria were established to facilitate risk assessment in the older population and are particularly valuable when dosing medications in patients or clients who are over 65 years of age. When patient/client within this demographic, the Criteria should be taken into consideration.

- Medications for patients or clients with preexisting hepatic or renal conditions:

According to Garza et al. (2023), when caring for patients or clients with hepatic or renal disease, whether is mild or acute, such as acute renal failure, nurses must consider the fact that drug elimination may be affected or severely impaired depending on each patient’s diagnosis. Drug doses may need to be reduced (and/or dosing frequency adjusted), and some drugs may even need to be discontinued. If a drug is administered to patients or clients with such conditions, the nurse should vigilantly be carefully monitor for adverse effects.

1.3 Pharmacodynamics

Pharmacodynamics is the field of study that governs the relationship between the plasma concentration levels of a drug and the body’s response to that drug. In simplified terms, pharmacodynamics examines the effect of a drug on the body.

Pharmacodynamics is the field of study that governs the relationship between the plasma concentration levels of a drug and the body’s response to that drug. In simplified terms, pharmacodynamics examines the effect of a drug on the body.

These are the fundamental components of pharmacodynamics:

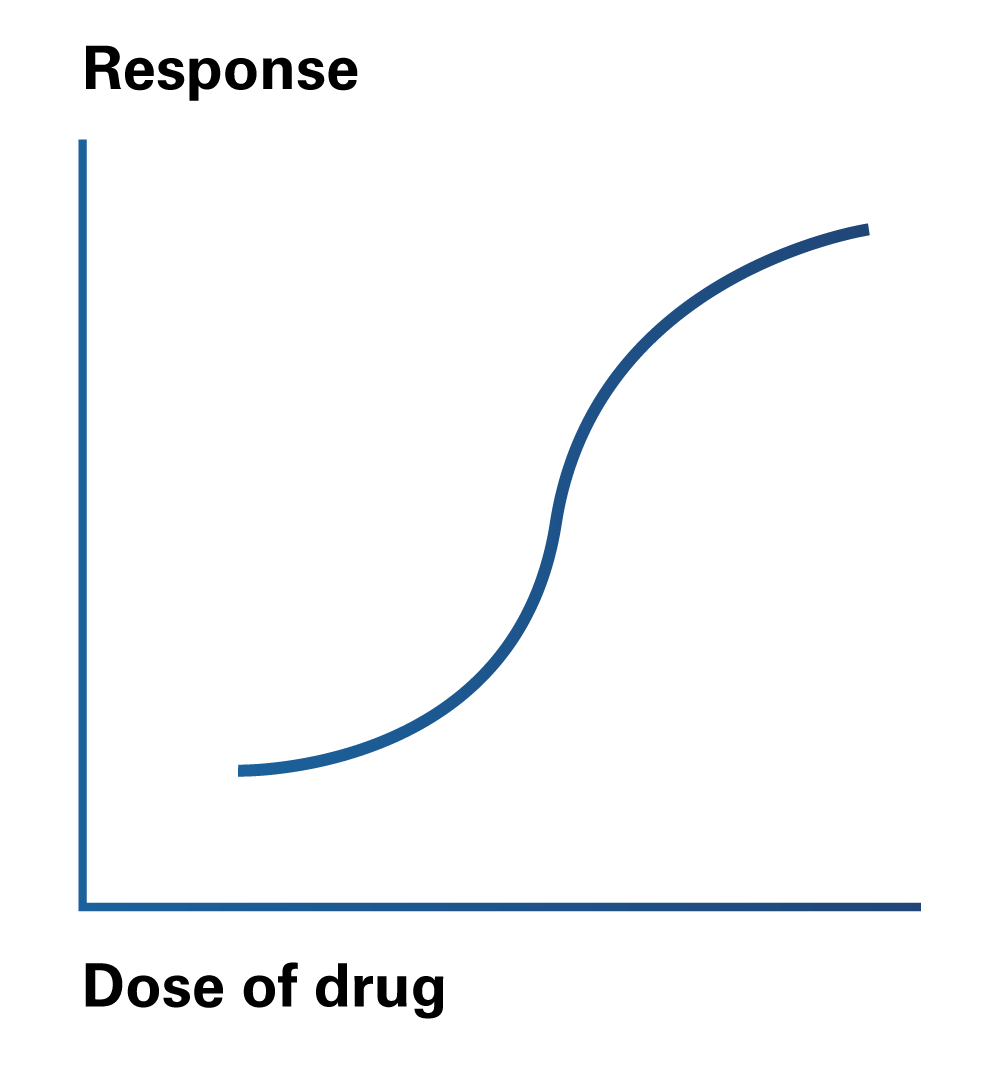

- Affinity is described as the drug’s ability to bind a receptor. The stronger the dose-response curve, the greater the affinity for a receptor.

- Efficacy measures how well a drug produces the desired pharmacological response. Returning to the dose-response curve, the higher the curve, the greater the efficacy.

- Potency is the amount of drug required to achieve the desired pharmacological effect. On a graded dose-response curve, the closest it is to the y-axis, the more significant the effect.

Figure 2

Drug Response to Dosage

A drug that binds to a receptor, alters its conformation and initiates a response such receptors’ function is referred to as an Agonist. On the other hand, a drug that binds to a receptor and prevents or impedes the activation of the receptor is known as an Antagonist.

Dose

The dose is the required amount of drug in weight, molecules or moles that will produce a desired effect. The physician is responsible for prescribing the dose, but it is the nurse’s duty to verify its accuracy and availability in the pharmacy. If necessary, the nurse should inform the physician about the need to adjust the dose.

When the dose is used to achieve the desired clinical response, it is referred to as a therapeutic dose, which may vary from person to person.

- Single dose: A single administration of medication through any route.

- Daily dose: The quantity of drug administered in 24-hour period, which can be given all at once or in multiple intakes (e.g., BID, twice a day).

- Total dose: The complete amount of drug required to achieve the therapeutic effect. For example:

- Amoxicillin and clavulanate 875/125 mg BID for 7 days.

- Loading dose: A large initial dose of a drug administered to rapidly achieve effective plasma concentration levels. It is mostly given intravenously, typically in critical care or emergency settings.

- Maintenance dose: The amount of drug needed to maintain a consistent level of drug concentration in the plasma.

Drug Names

All drugs have a chemical name, a generic name, and a brand name.

All drugs have a chemical name, a generic name, and a brand name.

- The chemical name of a drug consists of the precise chemical composition of the medication, including the arrangement of atoms. The good news is that, as a nursing student and a practicing nurse, it is not necessary to memorize chemical names. For example, the chemical name of Ibuprofen is 2-(p-isobutylphenyl) propionic acid.

- The generic name of a drug can be used by any country or manufacturer, and the first letter of that drug name is not capitalized because it is not a proper noun. For NCLEX purposes, the focus should be on the generic names of medications, as it may not always be provided with the brand name. For example, “ibuprofen” is the generic name for “Advil”.

- The use of a brand name of a drug is exclusive to the manufacturer of that drug, and it is capitalized as a proper noun. For example, “Advil” is just one brand name under which Ibuprofen is sold.

While pharmacology is a broad subject that delves deeply into molecules and biochemistry, the nurse’s primary objective is to ensure the patient/client receives the appropriate course of treatment based on the assessment by the multidisciplinary healthcare team. Through the nursing process, the nurse should ensure that the treatment aligns with the patient’s best interests and that all the conditions for treatment success are met.

While pharmacology is a broad subject that delves deeply into molecules and biochemistry, the nurse’s primary objective is to ensure the patient/client receives the appropriate course of treatment based on the assessment by the multidisciplinary healthcare team. Through the nursing process, the nurse should ensure that the treatment aligns with the patient’s best interests and that all the conditions for treatment success are met.

The nurse should possess knowledge of the most commonly administered drugs in the emergency room setting and medical/surgical floors, along with the overall interactions and possible side effects. This knowledge helps of the rest of the team identify any potential harm or increased benefits for the patient’s outcome.

- Chen, L., Giesy, J. P., & Xie, P. (2018). The Dose Makes the Poison. Science of the Total Environment, 621, 649-653.

- Cleveland Clinic. (2023). Beers Criteria. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/24946-beers-criteria

- Garza, A., Park, S.B., & Kocz, R. (2023, July 4). Drug Elimination. StatPearls Publishing. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31613442/

- Meloni, S., & Mastenbjörk, M. (2021). Pharmacology Review: A Comprehensive Reference Guide for Medical, Nursing, and Paramedic Students. Medical Creations Publishing.

- Ticho, A. L., Malhotra, P., Dudeja, P. K., Gill, R. K., & Alrefai, W. A. (2019). Intestinal Absorption of Bile Acids in Health and Disease. Comprehensive Physiology, 10(1), 21–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c190007

- Zerwekh, J., & Garneau, A. (2021). Mosby's Pharmacology Memory NoteCards: Visual, Mnemonic, and Memory Aids for Nurses (6th ed.). Elsevier.

The following links do not belong to Tecmilenio University, when accessing to them, you must accept their terms and conditions.

Videos

- Level Up RN. (2023, January 16). Pharmacokinetics: Nursing Pharmacology [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_t92gO0fFOU

- Simple Nursing. (2022, December 21). Pharmacokinetics Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion | Made Easy [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3S20pnv28ys

La obra presentada es propiedad de ENSEÑANZA E INVESTIGACIÓN SUPERIOR A.C. (UNIVERSIDAD TECMILENIO), protegida por la Ley Federal de Derecho de Autor; la alteración o deformación de una obra, así como su reproducción, exhibición o ejecución pública sin el consentimiento de su autor y titular de los derechos correspondientes es constitutivo de un delito tipificado en la Ley Federal de Derechos de Autor, así como en las Leyes Internacionales de Derecho de Autor.

El uso de imágenes, fragmentos de videos, fragmentos de eventos culturales, programas y demás material que sea objeto de protección de los derechos de autor, es exclusivamente para fines educativos e informativos, y cualquier uso distinto como el lucro, reproducción, edición o modificación, será perseguido y sancionado por UNIVERSIDAD TECMILENIO.

Queda prohibido copiar, reproducir, distribuir, publicar, transmitir, difundir, o en cualquier modo explotar cualquier parte de esta obra sin la autorización previa por escrito de UNIVERSIDAD TECMILENIO. Sin embargo, usted podrá bajar material a su computadora personal para uso exclusivamente personal o educacional y no comercial limitado a una copia por página. No se podrá remover o alterar de la copia ninguna leyenda de Derechos de Autor o la que manifieste la autoría del material.