Physiological Adaptation / 06

Make sure to:

- Recall necessary knowledge to determine clients’ needs for hydration and electrolytes.

- Determine techniques and methods to assess clients’ symptoms and parameters.

- Quote evidence-based nursing interventions to assist the client with fluid and electrolyte imbalances.

Around 52-60% of the body of a human adult is made up of water, along with ions which are distributed in both the extracellular and intracellular space, which helps maintain the body’s homeostasis (Lewis, 2022). The fluids in the intracellular space, which represent around 40% of the total body weight, are composed of ions such as sodium, potassium, and magnesium. The fluids in the extracellular space, representing 20% of the total body weight, contain ions and substances like chloride, bicarbonate, calcium, and sodium, as well as glucose (Brinkman et al., 2023). Alterations in the volume of fluids or their electrolyte composition may be due to problems in intake, elimination, or imbalance in bodily demands. These changes can have repercussions on the body's functioning and can be fatal if not treated promptly. In this learning experience, the learner will discuss the main symptoms of fluid and electrolyte imbalance in patients and explain the physiological principles to determine care actions based on scientific evidence.

Around 52-60% of the body of a human adult is made up of water, along with ions which are distributed in both the extracellular and intracellular space, which helps maintain the body’s homeostasis (Lewis, 2022). The fluids in the intracellular space, which represent around 40% of the total body weight, are composed of ions such as sodium, potassium, and magnesium. The fluids in the extracellular space, representing 20% of the total body weight, contain ions and substances like chloride, bicarbonate, calcium, and sodium, as well as glucose (Brinkman et al., 2023). Alterations in the volume of fluids or their electrolyte composition may be due to problems in intake, elimination, or imbalance in bodily demands. These changes can have repercussions on the body's functioning and can be fatal if not treated promptly. In this learning experience, the learner will discuss the main symptoms of fluid and electrolyte imbalance in patients and explain the physiological principles to determine care actions based on scientific evidence.

1.1. Identifying Signs and Symptoms of Client Fluid and/or Electrolyte Imbalance

Alterations in fluids and electrolytes can have fatal consequences if they are not treated promptly. That is why a patient must be evaluated thoroughly and carefully, taking the necessary time to review their medical history, identifying subjective and objective data that might be of importance.

Alterations in fluids and electrolytes can have fatal consequences if they are not treated promptly. That is why a patient must be evaluated thoroughly and carefully, taking the necessary time to review their medical history, identifying subjective and objective data that might be of importance.

Regarding the volume of fluids in the system, there could be a deficit (known as dehydration or hypovolemia) or an excess (known as overhydration or hypervolemia).

A patient experiencing dehydration (hypovolemia) might present signs and symptoms such as:

- Thirst

- Decreased sweating

- Dry, sticky mucous membranes

- Dry and not turgent skin

- Capillary refill over 2 seconds

- Peripheral pulses

- Feeling tired

- Irritability

- Dizziness

- Headache

- Sunken eyes

- Dark urine

- In infants: crying without tears or sunken fontanel

- Tachycardia

- Decreased urine production

The National Early Warning Score (NEWS) mnemonic is useful for initial and continuous evaluations to assess the recovery of the patient. It considers certain parameters and aims to detect early signs of clinical deterioration.

These parameters are:

- Respiration rate

- Oxygen saturation

- Systolic blood pressure

- Pulse rate

- Level of consciousness or new confusion

- Temperature

Obtaining a score of 5 or greater suggests that the patient has hypovolemia (Castera & Borhade, 2023). This score is intended to facilitate early intervention and improve patient outcomes by providing a standardized approach to monitoring and responding to changes in a patient’s condition.

It is crucial for nurses to assess urine output in patients at risk of hypovolemia. If a patient demonstrates less than 30 mL/hour (or 0.5 mL/kg/hour) of urine output over eight hours, the provider should be notified for prompt intervention (Lewis, 2022).

Laboratory findings expected in patients with hypovolemia are an increased blood urea nitrogen/creatinine ratio (BUN/Cr), transaminase levels, and hematocrit.

For patients with overhydration (or hypervolemia), expected signs and symptoms include hypertension, pitting edema, ascites, dyspnea, and in more severe cases, pulmonary crackles and distended jugular veins.

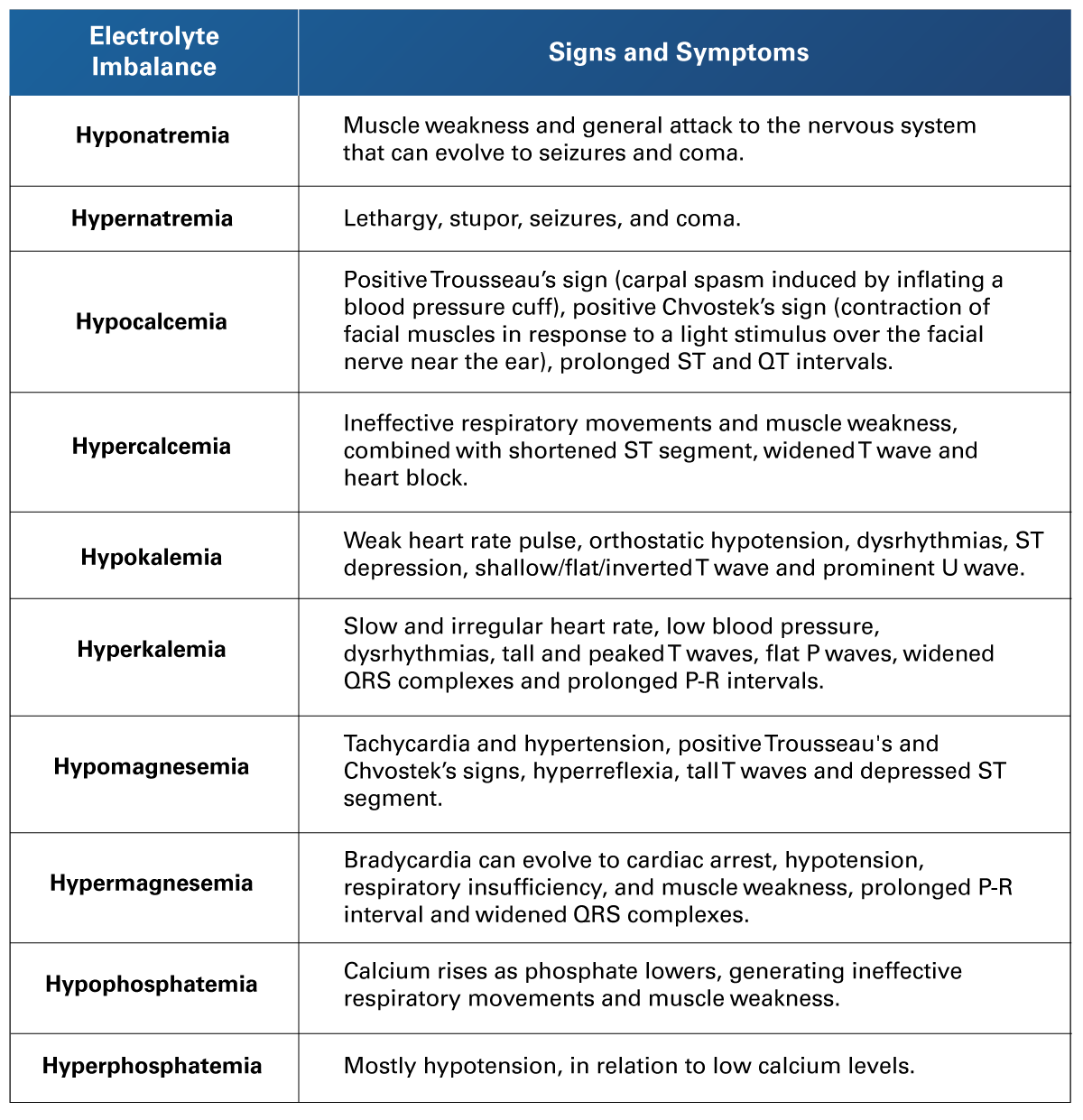

Concerning disorders related to deficit or excess of electrolyte concentrations, the prefixes hypo- and hyper- are used before the root element that is altered. The most common signs and symptoms, as described by Silvestri et al. (2021), for these unbalances are as follows:

Table 1

Common Signs and Symptoms for Electrolyte Imbalances

Adapted from Silvestri et al. (2021). Saunders Comprehensive Review for the NCLEX-PN Examination. Elsevier.

Adapted from Silvestri et al. (2021). Saunders Comprehensive Review for the NCLEX-PN Examination. Elsevier.

1.2 Applying Knowledge of Pathophysiology when Caring for The Client with Fluid and Electrolyte Imbalances

During the day, an average adult drinks 2,500 mL of liquid and eliminates the same amount, carrying out a series of processes that regulate the balance between fluid volume and electrolyte concentration (Lewis, 2022). Considering that 60% of the total body mass is composed of water, it is vital to understand the regulation systems that exist to balance out the distribution of this water and its contents, such as electrolytes, proteins, and other particles that pass through semipermeable membranes. As different conditions arise from specific fluid and/or electrolyte imbalances, the nursing professional must comprehend the nature of the general principles related to these exchanges to provide the best and according to care.

During the day, an average adult drinks 2,500 mL of liquid and eliminates the same amount, carrying out a series of processes that regulate the balance between fluid volume and electrolyte concentration (Lewis, 2022). Considering that 60% of the total body mass is composed of water, it is vital to understand the regulation systems that exist to balance out the distribution of this water and its contents, such as electrolytes, proteins, and other particles that pass through semipermeable membranes. As different conditions arise from specific fluid and/or electrolyte imbalances, the nursing professional must comprehend the nature of the general principles related to these exchanges to provide the best and according to care.

The distribution of fluids on the body occurs in the intracellular and extracellular spaces. Extracellular fluids, distributed as transcellular fluids, include cerebrospinal fluid, ocular fluid, pericardial fluid, intrapleural fluid, synovial fluid, gastrointestinal fluid, urine, serous fluid, fluids within serous membranes of body cavities, perilymph, endolymph of the inner ear, and intravascular fluids within arteries, veins, and capillary networks.

The distribution of ions occurs in both types of fluids mentioned. Intracellular fluids contain magnesium, potassium, and phosphate, while extracellular fluids might contain calcium, chlorine, bicarbonate, glucose, or sodium. These different molecules determine the osmolarity, which is “the concentration of a solution, expressed as the total number of solute particles per liter” (Oxford University Press, 2023). Normal osmolarity (also known as iso-osmolarity) is typically around 286 milliosmoles per kilogram (mOsm/kg). It is mainly determined by sodium, glucose, and urea. Values under 280 mOsm/kg are considered hyposmolar and those over 295 mOsm/kg are hyperosmolar.

Fluid movement between the intracellular, interstitial, and intravascular compartments is driven by the concentration of solutes, a process known as osmosis (Lewis, 2022). Fluids cross the membranes of the cells, to exchange between the intracellular and the extracellular spaces, taking solutes with them, and this happens in two distinct mechanisms: passive transport (which involves the passage of molecules from a place of high osmolarity to another with less osmolarity) and active transport (when the molecules pass from a place with low osmolarity into another with higher osmolarity). An example of active transport happens with the sodium-potassium pump, which transports potassium (K) ions into the cell while transporting sodium (Na) ions outside of it. When two spaces have the same osmolarity, they are described as being iso-osmolar.

Inside the intravascular space, a particular thing happens, since fluids remain inside the space due to the presence of albumin protein, which has a high osmolarity and exerts a pull force for liquids. This is known as oncotic pressure. When albumin levels are low, liquids tend to pass to the extravascular space in passive transport.

As an opposing force to oncotic pressure, hydrostatic pressure is the one a contained fluid exerts on the walls of the space containing it. In the human body, blood pressure is determined by the pressure exerted by blood on the walls of blood vessels, the resistance of these vessels, and the contractility of the myocardial muscle (Lewis, 2022). Considering that an average adult has 4.5 to 6 liters of total blood, a decrease in this volume would lead to reduced hydrostatic pressure and, consequently, lower arterial blood pressure values.

Most of the fluids are eliminated from the body by urine through a process called filtration, where hydrostatic pressure pushes fluids and solutes through the membrane toward the kidney to eliminate toxic substances and excess of fluids. The other type of elimination of fluids is “insensible losses” that are liquids present in stool, perspiration, and respiration (Lewis, 2022). Patients with drugs such as diuretics increase the loss of fluids by urine. Persons working in high temperatures or patients with fiber, burns, or mechanical ventilation increase their insensible losses.

Water volume balance is regulated by several mechanisms, including thirst, antidiuretic hormone (ADH), and the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS).

The first, thirst, is a nervous system response that results from low fluid volume in the organism. Secondly, the antidiuretic hormone (ADH) is produced as a response by osmoreceptors located in the hypothalamus when osmolarity levels of the serum increase. Lastly, the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS) is a biochemical axis that causes vasoconstriction to increase hydrostatic pressure and secure blood flow to vital organs. Its last element, aldosterone, is a steroid hormone released by the adrenal cortex that causes sodium reabsorption in kidneys, increasing serum osmolality and blood pressure (Lewis, 2022).

Attending the general reasons for low levels of fluids (hypovolemia), it is mostly caused by inadequate oral fluid intake, the use of diuretics, prolonged exposure to the sun, high temperatures, bleeding, water loss due to vomiting/diarrhea/fever, or loss through the skin as it occurs in burns or big abrasions. Those at a higher risk of dehydration are infants and children, due to their immature nervous system regulation, or elderly people, because of age-related impairment in thirst perception. Also at risk are patients with diabetes or kidney diseases. If left unattended, hypovolemia may lead to hypoperfusion of vital organs and hypotension (Lewis, 2022).

In contrast, high levels of fluids (hypervolemia) commonly occur due to heart failure, kidney failure, cirrhosis, or pregnancy. This state of overload can cause hypertension and increase cardiac output, which may lead to heart and lung failure.

Switching to aspects pertaining to electrolytes, it must be noted that sodium is the most relevant one of them since it plays an important role through the sodium-potassium pump, which causes the contraction of all body muscles (including cardiac and respiratory muscles). As stated, sodium also determines the overall osmolarity of blood, along with glucose and urea.

The normal values of plasma osmolality are from 275 mOsm/kg to 290 mOsm/kg, and normal values for sodium are 136 to 145 mEq/dL (Lewis, 2022).

Hyponatremia is defined when sodium values are 136 mEq/dL or less. Depending on the fluid volume, hyponatremia can exist as hypovolemic, hypervolemic or euvolemic.

Hypovolemic hyponatremia can result from gastrointestinal fluid loss (due to diarrhea or vomiting), diuretics, osmotic diuresis, salt-wasting nephropathies, cerebral salt-wasting syndrome (like urinary salt wasting, possibly caused by increased brain natriuretic peptide), or a mineralocorticoid deficiency. Low sodium intervenes in the nervous system, which can cause confusion or headaches. Also, the muscular system is affected, causing bradycardia (heart rate under 60 beats per minute), and bradypnea (respiratory rate under 12 per minute). If this condition is not treated, it can evolve into seizures, coma, pulmonary arrest, or cardiac arrest. In adrenal insufficiency and hypothyroidism there are an increment on vasopressin which can cause hypovolemic hyponatremia due the loss of intravascular volume and hypervolemic hyponatremia due the loss of effective intravascular volume

Hypervolemic hyponatremia can also be caused by acute or chronic renal failure, nephrotic syndrome, congestive heart failure, cirrhosis, or iatrogenic causes.

Euvolemic hyponatremia can be caused by various drugs, including oxytocin, desmopressin, antidepressants, morphine, certain opioids, carbamazepine, and analogs such as vincristine and nicotine. Antipsychotics, chlorpropamide, cyclophosphamide, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and illicit substances like methylenedioxymethamphetamine (commonly known as ecstasy) can also contribute. Some medical conditions that can cause this include Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone (SIADH), Addison's disease, hypothyroidism, high fluid intake with low solute intake, and iatrogenic factors.

Based on the serum’s osmolality, hyponatremia can furthermore be categorized as hypotonic, hypertonic, and isotonic. Hypotonic hyponatremia is characterized by an osmolarity under 275 mOsm/kg. Hypertonic hyponatremia is registered over 290 mOsm/kg and can be seen in cases of hyperglycemia. Finally, isotonic hyponatremia consists of an osmolarity between 275 and 290 mOsm/kg. For patients with hypertriglyceridemia, cholestasis, and hyperproteinemia, it is important to note that their laboratory results may show no alteration in osmolarity; however, these conditions can lead to a decrease in sodium levels.

As a final consideration, high levels of sodium are known as hypernatremia and are defined as values equal to or greater to 145 mEq/dL. This state may cause abrupt brain cell shrinkage, which leads to lethargy, confusion, hyperreflexia, or even seizures. If this condition is not treated, it can evolve into cerebral edema, coma, arrhythmia, pulmonary or cardiac arrest. The treatment for hypernatremia includes overhydration if dehydration is a contributing factor, along with sodium restriction (Gaie et al., 2023).

1.3 Managing Care of a Client with Fluid and Electrolyte Imbalance

Prompt detection and correction of fluid and electrolyte imbalances are crucial for the patient's recovery and the preservation of life. All health team members must pay special attention to the patient's history to identify possible causes for fluid imbalances, including diseases, treatments, lifestyles, or triggering events. The actions to be taken are specific to each type of imbalance.

Prompt detection and correction of fluid and electrolyte imbalances are crucial for the patient's recovery and the preservation of life. All health team members must pay special attention to the patient's history to identify possible causes for fluid imbalances, including diseases, treatments, lifestyles, or triggering events. The actions to be taken are specific to each type of imbalance.

For patients experiencing dehydration (hypovolemia), actions should include increasing water intake and administering formulas with electrolytes. If the patient is in hypovolemic shock without a bleeding source, they should receive a rapid infusion of a warm isotonic crystalloid solution at 30 mL/kg of body weight, administered as a 500 mL bolus; in case there is bleeding, it should be controlled as fast as possible, preferring blood products over crystalloids and applying a balance transfusion using 1:1:1 or 1:1:2 ratios of plasma to platelets to packed red blood cells. Also, administering antifibrinolytics during the following 3 hours is advised, avoiding vasopressors due to their effect on perfusion (Sharven et al., 2023).

Patients presenting overhydration (hypervolemia) most likely experienced sodium retention due to kidney or heart failure. Their treatment involves sodium restriction.

Regarding an inferior concentration of sodium (hyponatremia), this state can exist with regular, decreased or increased volume. Euvolemic hyponatremia is treated with correction of the origin cause and specific correction with sodium equivalents. Hypovolemic hyponatremia is treated with oral hydration, which can be with sports drinks at the early stage, IV solutions for advanced stages, and sodium corrections with sodium equivalents in emergency cases. The treatment for hypervolemic hyponatremia consists of diuretics and corrections with sodium equivalents.

The deficiencies of electrolytes are defined at specific values for each solution. Hypomagnesemia is defined as levels below 1.8 mEq/L (0.74 mmol/L). Hypokalemia occurs at levels of 3.5 mEq/L or lower. Hypophosphatemia is identified at levels below 3.0 mg/L. Hypocalcemia begins at levels under 9.00 mg/dL. The treatment for any of these involves correcting the central cause and administering the deficient component.

The deficiencies of electrolytes are defined at specific values for each solution. Hypomagnesemia is defined as levels below 1.8 mEq/L (0.74 mmol/L). Hypokalemia occurs at levels of 3.5 mEq/L or lower. Hypophosphatemia is identified at levels below 3.0 mg/L. Hypocalcemia begins at levels under 9.00 mg/dL. The treatment for any of these involves correcting the central cause and administering the deficient component.

Conversely, high electrolyte levels, such as hypermagnesemia (12.6 mEq/L or 1.07 mmol/L or higher), hyperkalemia (5 mEq/L or greater), hyperphosphatemia (4.5 mg/dL or higher), and hypercalcemia (10.5 mg/dL or higher), are treated with IV solutions and diuretics to rapidly eliminate the excess. Calcium gluconate is the antidote for magnesium overdose.

As stated by Castera and Borhade (2023), IV solutions are used in the treatment of fluids and electrolytes. These are divided into three main types due to their osmolarity: hypotonic, hypertonic and isotonic.

Hypotonic solutions have a lower osmolarity than blood due to their lower concentration of dissolved solutes. These are used to treat cellular dehydration. A commonly used hypotonic solution is 0.45% NaCl, also known as Half Normal Saline.

Hypertonic solutions have a greater concentration of dissolved solutes than blood, so their osmolarity is higher. Commonly used hypertonic solutions include 3% NaCl (Normal Saline), 10-15% dextrose in water, and 5% sodium bicarbonate.

Isotonic solutions have a similar concentration of dissolved solutes as blood, resulting in a comparable osmolarity. When administering IV treatment without modifying osmolarity, 0.9% NaCl, known as Normal Saline, is a commonly used isotonic solution.

Nurses must administer the IV solution, carefully measuring the prescribed amounts and timing, and monitor the patient for effects of the medication, being prepared for possible reactions such as tachycardia, dyspnea, or seizures. Enteral tubes, such as nasogastric or orogastric tubes, can also be used to administer solutions. In some cases, intraosseous access may also be required.

1.4 Evaluating Client’s Response to Interventions to Correct Fluid or Electrolyte Imbalance

In all previously mentioned medical conditions, close monitoring of certain parameters is essential to ensure the correct development of treatment and to enable nursing staff to intervene in case of any sudden complications. These parameters include respiratory rate, heart rate, blood pressure, body weight, urine output, mental status, and observation of any peripheral edema. Vital signs should be reevaluated after each intravenous bolus administration to assess and rule out any risk of pulmonary edema. Nursing professionals are also expected to assess whether the patient is maintaining a balanced fluid intake and output and to evaluate for the presence of phlebitis or any other complications that may arise from IV administration of solutions or drugs.

In all previously mentioned medical conditions, close monitoring of certain parameters is essential to ensure the correct development of treatment and to enable nursing staff to intervene in case of any sudden complications. These parameters include respiratory rate, heart rate, blood pressure, body weight, urine output, mental status, and observation of any peripheral edema. Vital signs should be reevaluated after each intravenous bolus administration to assess and rule out any risk of pulmonary edema. Nursing professionals are also expected to assess whether the patient is maintaining a balanced fluid intake and output and to evaluate for the presence of phlebitis or any other complications that may arise from IV administration of solutions or drugs.

The National Early Warning Score (NEWS) mnemonic is useful for initial and for continuous evaluations to assess the recovery of the patient. It is good practice to monitor electrolyte and pH values in these patients. It will require comparing any new values with past records, to establish a pattern of clinical evolution. Modifying the patient’s diet may be necessary, including increasing or decreasing the amounts of sodium, calcium, potassium, phosphate, or total fluids provided.

Patients experiencing loss of fluid volume or electrolyte concentration often have rapidly changing clinical conditions. That is why it must be detected and treated in a timely manner. Throughout the treatment, close monitoring of the patient’s response is crucial to prevent the development of any additional problems. Due to the potential for drastic changes over a short period, frequently recording and analyzing fluid intake and excretion is also an important part of nursing care for these patients.

Patients experiencing loss of fluid volume or electrolyte concentration often have rapidly changing clinical conditions. That is why it must be detected and treated in a timely manner. Throughout the treatment, close monitoring of the patient’s response is crucial to prevent the development of any additional problems. Due to the potential for drastic changes over a short period, frequently recording and analyzing fluid intake and excretion is also an important part of nursing care for these patients.

- Brinkman, J., Dorius, B., & Sharma, S. (2023). Physiology, Body Fluids. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482447/

- Castera, M., & Borhade, M. (2023). Fluid Management. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532305/

- Giae, Y., Seon, H., & Sejoong, H. (2023). Evaluation and Management of Hypernatremia in Adults: Clinical Perspectives. Korean Journal of Internal Medicine, 38(3), 290-302. https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2022.346

- Lewis, J. (2022). About Body Water. MSD Manual Consumer Version. https://www.msdmanuals.com/home/hormonal-and-metabolic-disorders/water-balance/about-body-water

- Oxford University Press. (2023). Osmolarity. Oxford English Dictionary. https://www.oed.com/search/dictionary/?scope=Entries&q=osmolarity

- Sharven, T., Aussama, K. N., & Reza, A. (2023). Hypovolemic Shock. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513297/

- Silvestri, L. A., Silvestri, A. E., Grewal, A., & Gim, J. (2021). Saunders Comprehensive Review for the NCLEX-PN Examination (9th ed.). Elsevier.

The following links do not belong to Tecmilenio University, when accessing to them, you must accept their terms and conditions.

Readings

- Barlow, A., Barlow, B., Tang, N., Shah, B. M., & King, A. E. (2020, December 1). Intravenous Fluid Management in Critically Ill Adults: A Review. Crit Care Nurse, 40(6), e17–e27. https://doi.org/10.4037/ccn2020337

Videos

- DrBruce Forciea. (2017, April 21). Fluids and Electrolytes: Water [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/VMxmDeduKR0

La obra presentada es propiedad de ENSEÑANZA E INVESTIGACIÓN SUPERIOR A.C. (UNIVERSIDAD TECMILENIO), protegida por la Ley Federal de Derecho de Autor; la alteración o deformación de una obra, así como su reproducción, exhibición o ejecución pública sin el consentimiento de su autor y titular de los derechos correspondientes es constitutivo de un delito tipificado en la Ley Federal de Derechos de Autor, así como en las Leyes Internacionales de Derecho de Autor.

El uso de imágenes, fragmentos de videos, fragmentos de eventos culturales, programas y demás material que sea objeto de protección de los derechos de autor, es exclusivamente para fines educativos e informativos, y cualquier uso distinto como el lucro, reproducción, edición o modificación, será perseguido y sancionado por UNIVERSIDAD TECMILENIO.

Queda prohibido copiar, reproducir, distribuir, publicar, transmitir, difundir, o en cualquier modo explotar cualquier parte de esta obra sin la autorización previa por escrito de UNIVERSIDAD TECMILENIO. Sin embargo, usted podrá bajar material a su computadora personal para uso exclusivamente personal o educacional y no comercial limitado a una copia por página. No se podrá remover o alterar de la copia ninguna leyenda de Derechos de Autor o la que manifieste la autoría del material.